Jólabókaflóð

It wouldn’t be Christmas Eve here at Book Barmy unless I posted this:

In Iceland, it is a Christmas Eve tradition to give a book as a gift.

This is called Jólabókaflóð, or the Christmas Book Flood.

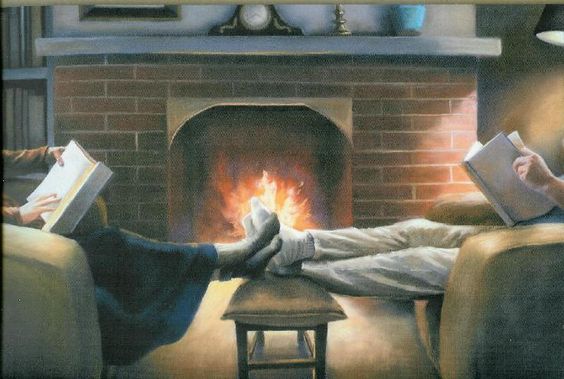

This time of year the sun doesn’t rise until 11 AM & it’s dark by 3 PM.…

So after a brisk (and chilly!) afternoon walk around town with the rest of their neighbors, familes snuggle into their homes with a hot drink and to read their new books.

Wishing all my fellow book lovers a traditional Jólabókaflóð

Merry Christmas and happy reading, from Book Barmy headquarters

This image from Deborah DeWitt – check out her book themed art HERE

This image from Deborah DeWitt – check out her book themed art HERE

Dear Santa,

I actually gasped when I saw this on the internet.

This historic bookshop and its contents are for sale.

So Santa if you’re checking your list, I’ve always dreamed of owning a bookshop, nothing too big, nothing too fancy. It would have a resident cat, comfortable chairs, coffee and tea for customers, the occasional author reading with wine, and a little children’s corner. No soaps, mugs or stuffed animals for sale–just books.

And, in my head, my little bookshop (aptly named Book Barmy) looks just like this.

But, it’s well known the second best way to throw money away is to own a bookshop (the first is owning a sail boat). And while this little place is only three hours from New York City, I can’t imagine hoards of customers. I remind myself of the weather (snow, ice) and bugs (mosquitoes, black flies) and go sit out on my deck for a great sunset here in California.

The full story is HERE and yes, I’m still sighing over the photos.

So if you’re stuck for a Christmas gift idea for that bibliophile on your list ~~ here you go. Hint hint hint.

Or, if you know a nicely wealthy book lover — pass this on.

This needs to stay a bookshop.

Baby, Just One More Page…

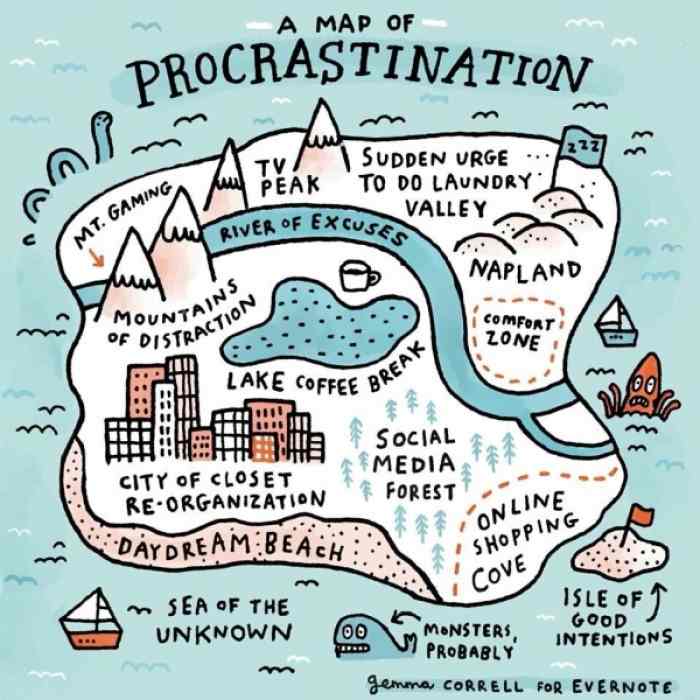

This is me right now…so much to do and yet I have some great reading taunting me…

You may have noticed the earth-shattering silence here on Book Barmy.

You may have noticed the earth-shattering silence here on Book Barmy.

I’ve fallen victim to a big procrastination funk. You may surmise it’s because of the holidays, which is part of it ~~ I have many festive things to do, along with those pesky everyday chores

But, suddenly Book Barmy has become one of those chores.

I have no good reason, no good excuse why I haven’t blogged. It’s not due to a lack of reading. I’ve read some books and enjoyed them – they’re stacked right here next to me — but somehow I just don’t have it in me to write about them.

To quote a fellow blogger (Vanessa), going through the same thing right now:

The cold hard truth is that I just didn’t feel like writing. I had no ideas, no drive, no inspiration — blogging almost started to feel like a form of punishment. So I stopped.

I don’t want Book Barmy to become either a chore or a burden, so I will be taking a small break…just to get my mojo back.

I’m still reading – that will never change.

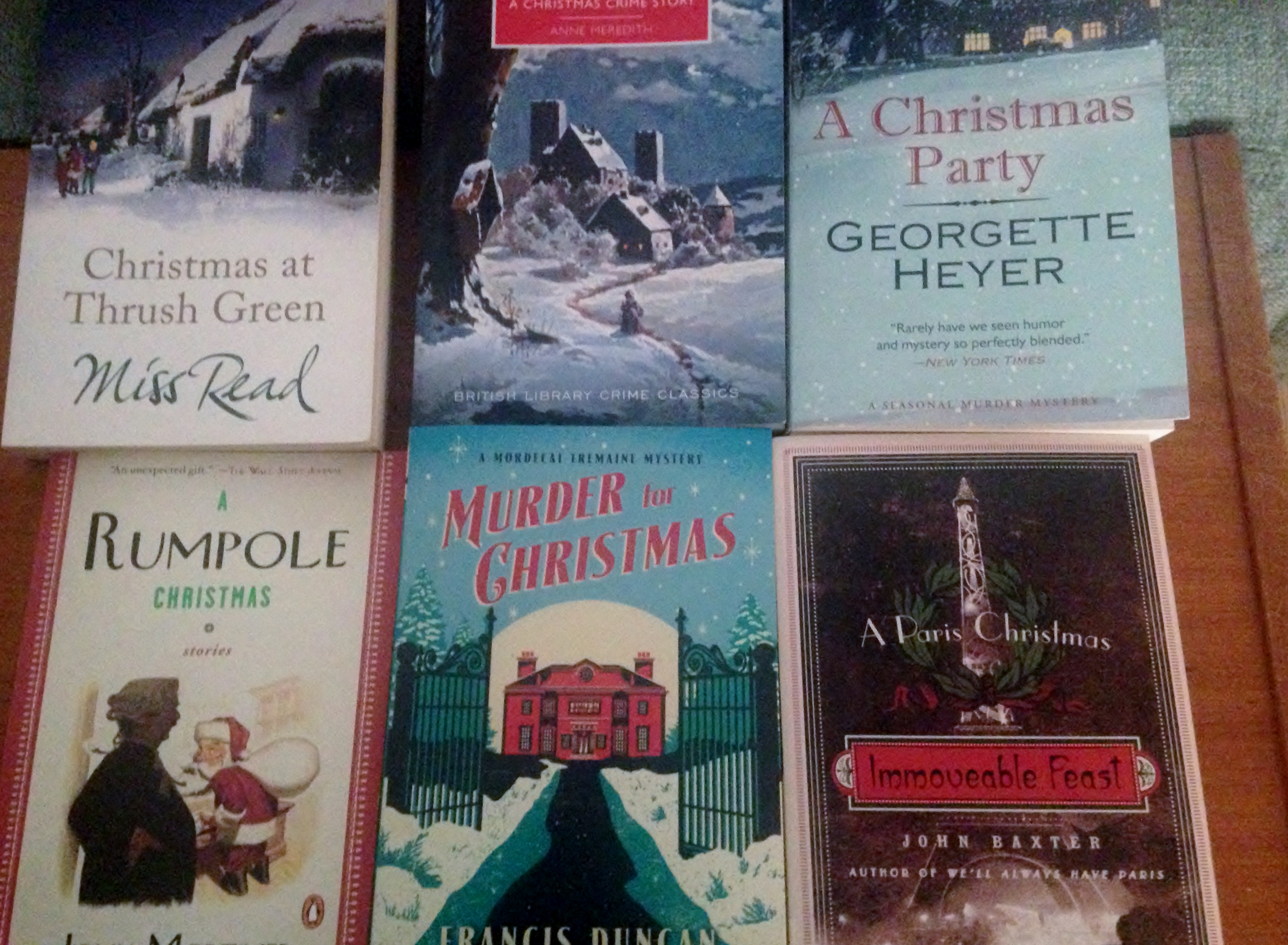

Here’s evidence — a collection of Christmas books I’ll be reading in the next few weeks.

But for now, I’m going to take a little break.

I appreciate your patience and understanding.

I’ll be back soon…

It’s Here!

Today’s the day – it’s finally here. As in previous years, I advised you to cancel your appointments, call in sick to work and to be at your local bookstore first thing this morning to buy the newest Louise Penny book — Kingdom of the Blind.

Today’s the day – it’s finally here. As in previous years, I advised you to cancel your appointments, call in sick to work and to be at your local bookstore first thing this morning to buy the newest Louise Penny book — Kingdom of the Blind.

Didn’t do any of that? Oh well, you’ll just have to swing by your bookstore on your way home.

Let me tell you why I’m being so bossy insistent about this.

Ms. Penny is a mystery writer with a trio of talents – not seen in very many mystery series writers.

First, she has keen sense of humans, their frailties, their emotions, their kindnesses and their dreadfulness. Her characters are multi-dimensional and fully realized. Second, Ms. Penny creates an all enveloping sense of place – her settings are always fall-into-the-page realistic — from the cozy bistro in Three Pines to the dirty, drug infested back streets of Montreal. Combine this with her page-turning, yet complex multi-layered, mysteries, and well you’ve got one of the best mystery series being published.

While you can read any of her novels as a standalone, I do suggest you try and read them in order as some of the story lines do carry into the next and the characters become more developed and evolved. You can see her whole series of books in order on her website – HERE

Kingdom of the Blind picks up a few months after the last book (Glass Houses). Armand Gamache was suspended as head of the Sûreté du Québec having deliberately allowed some seized opioids to slip though his hands in order stop an insidious street drug operation. Amelia Choquet, one of his cadets has just been kicked out of the police academy due to her own drug use and is now thrust back onto to the seedy, drug infested back streets of Montreal. A coincidence? We wonder…

Meanwhile, wintry Three Pines remains the idyllic oasis for its residents and friends. But they have lost power and are buried in snow:

Reine-Marie, at the bistro:

Why do we live here? Oh heaven…do you have power?

Non. A generator.

Hooked up to the espresso machine?

And the oven and fridge, said Gabri.

But not the lights?

Priorities, said Olivier. Are you complaining?

Mon Dieu, no, she said.

Comfort foods that rarely fail in their one great task are abundant.

Gamache, psychologist and bookseller Myrna Landers, and a young builder have been called to an abandoned farmhouse just outside Three Pines to meet with a notary. Once there, they find out they have been named the liquidators (executors) of a mysterious woman’s will. The three adult children, who are the beneficiaries, have no idea why their mother chose these three unknown people to oversee her will. It turns out there is more to the story than anyone thought — a family story of a lost European inheritance dating back hundreds of years, embezzlement, and murder.

Ms. Penny is a master of plotting and just when you think you know where she’s going (and if you’re like me, you dumbly believe you have it figured out) the plot twists in an unexpected direction. This had me flipping pages as fast as I could read, and yet I made myself slow down to savor the writing.

All Ms. Penny’s novels have a theme woven into her mysteries and this one is about blindness or our blind spots. How humans see what they want to see. Masterfully we are given insights into what at first seemed one thing and is reveled to be something else entirely. A drug wasted transvestite has goodness underneath. A beloved godfather has a nasty streak. A trusted financial advisor should, or should not, be trusted.

Don’t worry devoted Ms. Penny fans, the cast of characters is still there from Three Pines and there’s a smattering of Ruth chuckles — but this installment is especially focused on Gamache and his second in command (and now son-in-law) Beauvoir. Both are contemplative and confronting major decisions that will inspire life changing events. One of which is revealed in the last chapter and will have you wanting whatever is up next in this wonderful series.

I’m going to leave it here, no spoilers and I’m really at a loss to review The Kingdom of the Blind in the fashion it deserves, so I will quote one of my favorite professional reviewers, Maureen Corrigan:

Any plot summary of Penny’s novels inevitably falls short of conveying the dark magic of this series. No other writer, no matter what genre they work in, writes like Penny.

Kingdom of the Blind – don’t say no — just buy it.

Many (many) thanks to Minotaur Books for providing an Advanced Readers Copy.

The Little Stranger by Sarah Waters

The Little Stranger was a deliciously creepy Halloween read which kept me up well into several October nights — but I’m only now getting around to this review. Pretend it’s Halloween, which was only a few weeks ago.

The Little Stranger was a deliciously creepy Halloween read which kept me up well into several October nights — but I’m only now getting around to this review. Pretend it’s Halloween, which was only a few weeks ago.

It’s post-war Warwickshire, England and Dr. Faraday has been called to Hundreds Hall, the Ayres family mansion. The doctor was here before, as a child, accompanying his mother, a housemaid for the family. As a child he was entranced with the hall’s decorative wall panels and he secretly pried loose and pocketed a carved walnut.

Now it’s thirty years later and Hundreds Hall has lost former grandeur. In amongst leaky ceilings and musty carpets lives the Ayres family: Mrs. Ayres, a widow who longs for the old days of her family glory; her son, Roderick, a veteran who is still suffering both physically and mentally from the war, and his sister, Caroline, a young woman who desires a life of her own.

But the most important character is Hundreds Hall — the author spends pages (and pages) describing the crumbling and dilapidated mansion. This provides an eerie backdrop for presenting a family tormented by the past.

[When] I stepped into the hall the cheerlessness of it struck me at once. Some of the bulbs in the wall-lights had blown, and the staircase climbed into shadows. A few ancient radiators were bubbling and ticking away, but their heat was lost as soon as it rose. I went along the marble-floored passage and found the family gathered in the little parlour, their chairs drawn right up to the hearth in their efforts to keep warm.

The Ayres are stuck between the pre-war world and the post war one. But, as we discover, they are also stuck between this world and one inhabited by spirits and secrets.

Yes, the house is haunted — mysterious writing appears on the walls, there are unexplained small fires, unexpectedly locked rooms, and creepy noises through the antiquated pipes. Roderick succumbs to his demons (and the house’s) and is sent away to an institution. Carolyn struggles to maintain some sense of normalcy in the highly abnormal Hundreds Hall and Mrs. Ayres begins to go mad.

At the center is Dr. Faraday, attending each family member as best he can but also striving to get to the bottom of the frightening incidents at Hundreds Hall. Despite his lower class upbringing, Dr. Faraday not only becomes the family doctor, but also a trusted friend, and eventually, Caroline’s fiancée.

The prose beautifully builds a chilling atmosphere and a looming sense of dread. More eerie than scary. Slow and languid but at the same time, exciting and suspenseful. Although the novel could have benefited from some major editing, I was totally invested — reading on and on, even when I got slightly spooked — hearing things go bump in the night.

Some readers said there is no resolution – no ending. However, by re-reading several key scenes and the last few pages — I figured out who is the little stranger and had goosebumps along the way.

The Little Stranger is not at all like some of today’s merely adequately written thrillers, whose readers only require a ‘page turner’. This novel is slow, subtle, literate and requires a little more thought — a thinking reader’s thriller.

Once again, they’ve made a film from a book I’ve just read. It looks properly creepy and atmospheric.

Trailer HERE